What the Ukraine Crisis Means for Cyber Warfare

What the Ukraine Crisis Means for Cyber Warfare.

While Russia’s invasion of Ukraine rapidly unfolds, we sat down with Omree Wechsler, a senior researcher in TAU’s Yuval Ne’eman Workshop for Science, Technology and Security, to discuss the cyber security aspects of the conflict in Ukraine.

Omree, Ukraine’s vice prime minister recently said the country had launched an ‘IT army’ to combat Russia in cyberspace. How would you assess Ukraine’s cyber capabilities?

Several attempts were actually made to assess the national cyber power of states, however, Ukraine was not among them due to the lack of data. While the research community is still in the dark about Ukraine’s cyberspace capabilities, we can assume that due to the fact that Ukraine was targeted by Russian cyberattacks ever since the annexation of Crimea, their cyber defense teams should be highly experienced.

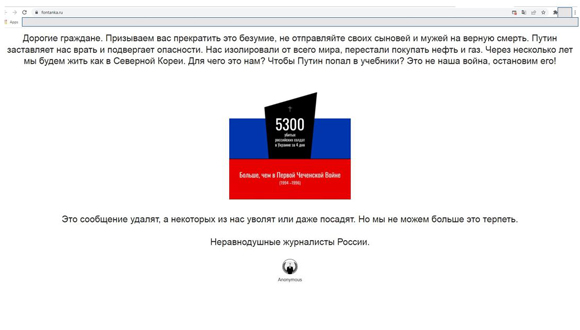

The Ukrainian government has called upon the country’s hacking community to help protect their infrastructure, conduct espionage and disruptive activities against Russian forces. In addition, certain international hacking collectives (such as Anonymous) declared that they would act against Russian targets.

Screenshot from a popular St. Petersburg news outlet (https://www.fontanka.ru/): On February 28, several Russian news sites were attacked, warning readers against “sending their sons and husbands to certain death.” Anonymous claimed responsibility

The official website of the Kremlin, the office of Russian President Vladimir Putin, kremlin.ru, crashed a few days ago (it is still down at the time of writing). Who is behind this attack?

The kind of attack we see on Russian official websites is called a ‘Denial of Service’ cyberattack (or DDoS). It’s a relatively easy task, and does not require sophisticated cyber expertise. Looking at past cyberattacks that were attributed to Western governments, mostly the U.S. Cyber Command, it does not seem that this is an instance of Western retaliation (Western cyberattacks would in theory look more like disabling military systems and so on), but rather the work of “hacktivists” – hackers who employ their capabilities as part of their social/political agenda. It could also be the work of Ukrainian hackers who took advantage of the opportunity to hit some symbolic target.

The power is no longer reserved for the state, then?

That’s correct. There are many other actors with access to cyber capabilities of varying complexity. However, advanced capabilities require means, such as money and expertise. Therefore, the most capable threat actor in this regard remains the state. It is also important to mention that cyber capabilities render factors such as population and geographic size, that are essential for conventional military might, obsolete.

I think that in the current conflict, international hackers or hacktivists could mostly embarrass the Russian government and cause some disruptions. One way that international hackers could cause damage to Russian targets is by ransomware attacks that encrypt data thus making it unreadable to the systems that use it. Another may include leaking highly sensitive or classified data that will be used by more sophisticated groups for more sophisticated attacks. However, the damage they can cause is usually limited compared to the capabilities of Western governments.

The Russian invasion disrupted Ukraine’s internet connectivity, but the country has successfully mobilized public opinion with the help of social networks, and its Vice Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov asked billionaire Elon Musk through Twitter to make available his company’s Starlink satellite broadband service in Ukraine. Musk delivered.

What type of cyber operations have been employed in this conflict?

Before the military attacks, the Russians also used DDoS attacks and flooded Ukrainian government and banking websites. Other attacks employed so-called ‘wipers’, a malware that deletes data and renders computers unusable. There are plenty of tools in the cyber toolbox.

What were the Russian objectives of the cyberattacks?

In January, some experts argued that the attacks’ objective was to steal information relevant to an upcoming invasion. DDoS attacks may have been used for diversion, while the wiper attacks prevented the Ukrainian government from quickly recovering by deleting data and preventing machines from booting.

The Russians also did their best to wreak fear and doubt among Ukrainian citizens and to embarrass the Ukrainian government. These attacks were accompanied with a constant disinformation campaign including reports on Ukrainian aggression in Eastern Ukraine.

Did it work?

There is no evidence that the attacks destabilized the public support for the Ukrainian government, inside Ukraine or abroad. It may seem that some of the Russian disinformation was also directed at local Russian citizens in order to increase support for the attack. There is still no indication that it worked, as reports on Russian soldiers that have been compelled to invade Ukraine are coming in.

Omree Wechsler

Should we expect more cyberattacks from Russia?

I believe Russian aggression in cyberspace will continue, in order to support its military operations. Cyberattacks that cripple the electric grid, water systems and other critical infrastructure are even more possible, given the fact that many critical systems in Ukraine use Russian technologies and software. A prime example, is Ukraine’s electrical grid which was built during Soviet times. It is very likely that many more malware infections are lying dormant in Ukrainian systems, ready to be deployed.

Russian threat actors will likely direct their cyber efforts against NATO and EU member states as well, in retaliation for supporting Ukraine and announcing sanctions. In fact, banks, critical infrastructure operators, government and public administration agencies in Europe and in the U.S. have been on alert for a while. Earlier this month, oil and fuel supply companies in Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium were hit by ransomware and forced to work in limited capacity. These attacks were attributed to a Russian-speaking group named ‘BlackCat,’ and, given that all these countries have in common that they are NATO member states that agreed to send troops and aircraft to countries surrounding Ukraine, it is difficult to decouple the attacks from the crisis in Ukraine.

Will the West remain idle?

Apart from sanctions, it is possible that the West will employ cyberattacks. According to reports, U.S. President Joe Biden was presented with various options to carry out cyberattacks aimed at disrupting the Russian invasion. The UK Defense Secretary, Ben Wallace, stated that the UK may launch cyberattacks on Russia if it targets the UK networks. However, given their sensitive position, Western responses in cyberspace are likely to be limited and reactive. It really depends on the purposes and gains they wish to achieve.

Theoreticians have long tried to define how cyberattack operations can be utilized amid political and military conflicts, and whether they stand on their own or support conventional military operations. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the months preceding, therefore, are bound to be investigated as case studies necessary to understand the nature of cyberwarfare operations.

Related posts